Contributing to that change are some of the proposed amendments to tax laws that the Biden administration has put forward, all of which have a myriad of effects beyond the specific law they target.

In a recent article, I took a look at the potential ramifications of the proposed 1031 repeal, which would change the way investors are taxed (or not taxed) for like-kind property exchanges.

That proposal, which was intended to secure more funding for the American Families Plan, could have a number of adverse consequences including reducing the flow of real estate transactions, culminating in a net negative economic effect.

Opportunity Zone Investing

The Opportunity Zone (OZ) program was created in 2017 as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The OZ strategy was developed to attract investment capital to census tracts that are characteristically below the national average for residential income.

In effect, investors are motivated to place powerful capital investments with more economically distressed census tracts in exchange for a reduction in tax liability on capital gains made on those investments.

For many years, OZ investments have succeeded in that initial aim; the program attracted significant capital investment within its first two years of existence, and White House Council of Economic Advisors estimates that as of the end of 2019, roughly 75 billion in equity capital was invested into qualified opportunity funds.

Thinking Twice

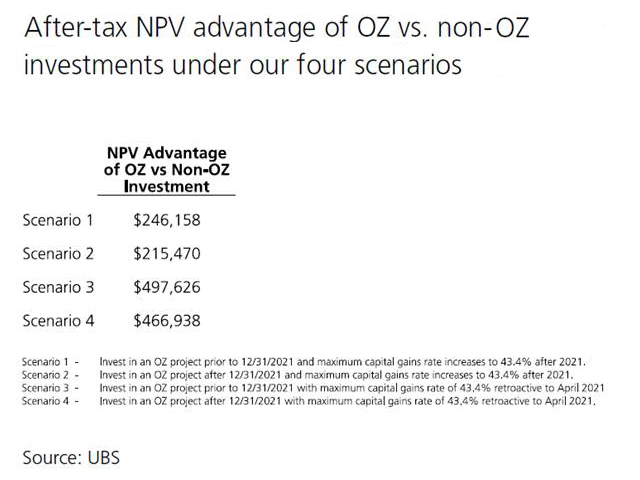

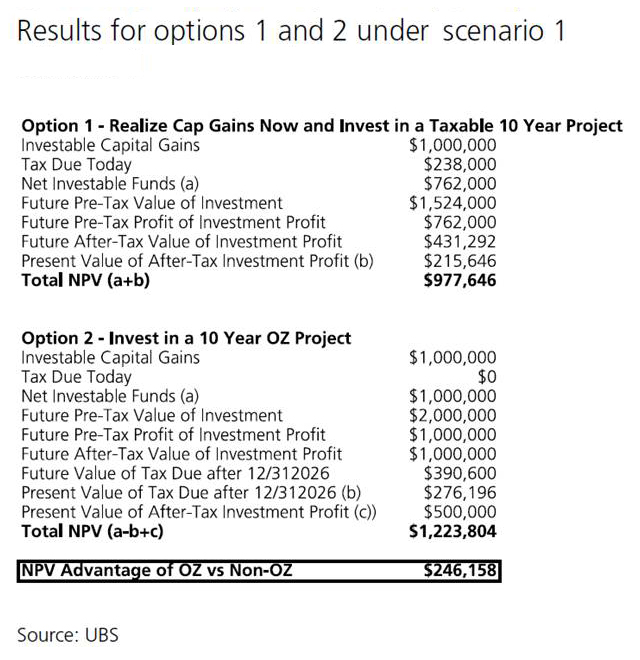

Experts at UBS went to the trouble of illustrating the consequences of rising capital gains taxes on the deferred liability strategy.

If an investor were to roll their existing gains into an opportunity zone project before the end of this calendar year, and if, for example, the maximum capital gain rate rose to 43.4%, the opportunity zone investors would have a 10% exclusion on the gains they would owe in 2026, five years later.

The additional gains that their investment generated within the OZ fund would be tax-free.

Their net profit value would be almost $250,000 higher than an investor who realized their capital gains now and invested in a taxable project that’s not in the opportunity zone space.

Here, the OZ strategy remains advantageous, but the margin of advantage is much smaller than it would normally be if capital gains taxes remained at a lower rate.

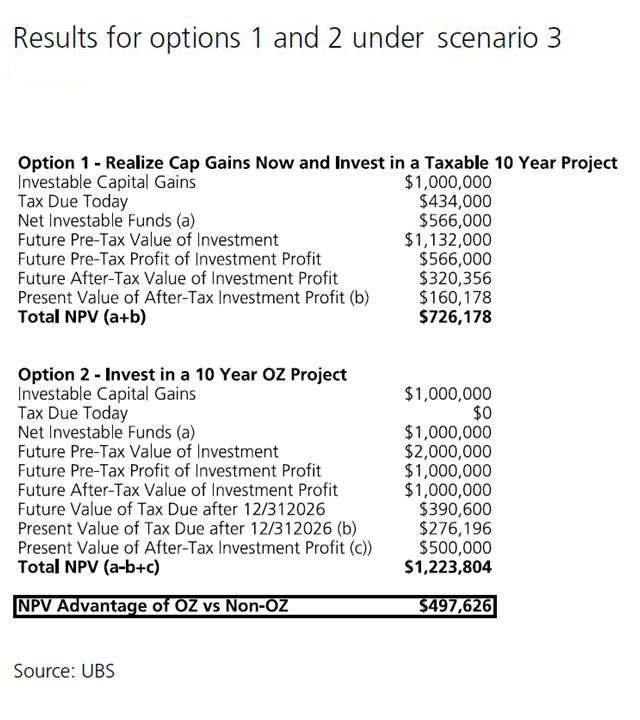

Throwing A Wrench—Retroactive Capital Gains Rates

If capital gains do increase this year, it’s possible that the change could be applied retroactively to impact investments made before December 2021.

In these cases, the investor whose capital gains are operating under the opportunity fund strategy is significantly advantaged.

Not only will they have the aforementioned 10% exclusion on the gains they would owe in the next five years, but the accrual of their investment in the opportunity fund would remain un-taxable.

Meanwhile, their non-opportunity zone peers would have to back track and pay their capital gains taxes at 43.4%. According to the in-depth analysis by UBS, that could mean an almost $500,000 advantage for net profit value advantage for the opportunity zone investor.

The investment ecosystem is fragile. It’s hard to know exactly which of the proposed tax changes will hold, and how exactly they’ll affect investment activity within the market. It’s been a positive part of the evolution of investment policy to have more capital flow in traditionally lower-income census tracts.